Creative Coding: Generating Banner Images

Creative Coding: Generating Banner Images

Shortly after revitalizing this blog, I also decided to join Mastodon as a way to provide updates on my blogging journey. As I was working on getting a verified badge for my site URL, I noticed the conspicuous absence of a banner image on my profile. I had my profile picture ready-to-go, but I've never needed a banner image before. What did I decide to do? Well, write some code of course!

Below, I'll talk through library/framework selection, my general thought process, and describe how I arrived at the (very) rough implementation I did. If you just want to see the code, that's here.

Picking a Theme

Ok, so I decided to generate some banner art. The question then is: what do I want to generate? I decided for now to keep it nice and simple, and reach for the tried and true Midpoint Displacement algorithm - in two dimensions, you might see this called the "Diamond-Square algorithm" (wiki).

Midpoint Displacement is a fairly low-effort way to get some decent looking mountains. Since it's a fractal algorithm, it works well for generating visuals without an obvious cyclic pattern. This tends to make better looking mountain silhouettes, than say, a composition of sinunsoids, which would appear much more regular.

A developer by the name of Paul Martz wrote up an excellent description of the algorithm in an article called "Generating Random Fractal Terrain". Unfortunately, the website hosting this article seems to have gone offline some time ago. Luckily, archive.org has plenty of captures. I probably would not trust any code downloads linked there to be valid, but the textual descriptions are still quite good.

Restating, I think, is one of the best ways to understand a concept, so I'll outline the algorithm in TL;DR fashion here:

- Start with a pair of points; at the min and max X-coordinate of your image, respecively

- Repeat some

Nnumber of times:- For each pair of points:

- Add a new point between the two, and displace this point on the Y-axis by some displacement amount

- Reduce the magnitude of the displacement amount using some smoothing factor

- For each pair of points:

Midpoint Displacement in Rust

Once I settled on what I wanted to generate, it was time to get some hands-on-keyboard time. One thing I really like to think about whenever I'm doing a project, in any language, is what the language and its ecosystem offers. When I first began this project, I went through a similar process with Rust. At the onset, I thought it might be neat to use pattern matching to recursively generate splits of line segments into smaller segments.

Initial Brainstorm

I brainstormed something like this:

Now, if you're an experienced Rustacean, you'll probably see a problem with this approach. If you're new to Rust, the issue might be lost on you because it's quite subtle. One of the things that Rust programmers need to be cognizant of is the size of data types. The compiler needs to be able to determine, at compile time, how much memory every instance of a given data type needs to allocate. Let's take a closer look at our implementation and try to figure that out.

So, for the case of a Segment, determining the data size is quite simple,

since it's two 32-bit floats, and those have a fixed size.

Now then, what about the memory required for a Node?

We could look at the simplest possible Node, which would look something like:

Node

Well, then we have a problem.

Since we could technically create a Path with of infinitely nested Nodes,

it's simply not possible to determine the size in this case.

The upper bound of our data type's size is infinite, and the compiler cannot

write an instruction to allocate infinite memory.

In fact, if we try to compile, the compiler helpfully informs us that this is

the case:

error[E0072]: recursive type `Path` has infinite size

--> src/lib.rs:1:1

|

1 | pub enum Path {

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^

2 | Segment(f32, f32),

3 | Node(Path, Path),

| ---- recursive without indirection

|

help: insert some indirection (e.g., a `Box`, `Rc`, or `&`) to break the cycle

|

3 | Node(Box<Path>, Path),

| ++++ +

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0072`.

The compiler also helpfully proposes a fix for us, using some indirection.

What this means, in other words, is to structure the data type in such a way

that a Node takes up a fixed size, by heap-allocating the inner Paths.

This turns them into pointers, which have a fixed size.

Ultimately, I decided against doing this. My reasoning was that I didn't think this design was actually going to provide me as much value as I initially thought. I might revisit this at a later point, but it was a fun diversion.

The Actual Approach

I ended up going with something a little more "traditional", for lack of a better term. This approach looks and feels a lot like what you might see in C++, Java, or other well-known languages. It's also not all that heavy on Rust language features, and has some panicking code sprinkled in, but that's all a future refactor waiting to happen.

For starters, I sketched out what I'd need to implement this algorithm. I landed on:

- a number of

steps(this isNin the pseudocode above) - an

initial_displacement, or how much noise there should be on the first recursive step - a

smoothnessvalue, or how much to reduce displacement per recursive level

That landed me on this function signature:

Let's unpack this.

We see here that our function takes the three parameters mentioned above, as well

as some rng (more on that shortly), and it returns a vector of f32.

As for implementation, we roughly want to do something like:

- start with an empty vector with enough capacity for

stepsnumber of subdivisions - populate the initial endpoints with a value (these will be the start and end of the vector)

- repeat

stepsnumber of times:- compute the midpoint for each pair of points

- displace the midpoint by a random amount, bounded by the current displacement

- reduce the displacement amount using

smoothness

Reading this over, we can see that we need some source of (pseudo-)randomness in

order to generate displaced midpoints.

That's where our parameter rng comes in, it's our source of (pseudo-)randomness.

The function signature includes this <R: Rng> - that's called a trait bound

in Rust.

What we're telling the compiler is that this function is generic over some type

R, and only types that implement the trait Rng are valid.

What is Rng, you may ask? It's the core trait in the very popular

rand

crate in the Rust ecosystem.

Ok, now that we've squared that away, let's talk implementation details.

Since I planned on implementing this as a recursive function, I went with the

tried and true pattern of creating a "wrapper" function that computes all the

initial state, and an additional function that does the recursive step.

I sketched out this signature for the recursive step, which I called fill:

A couple of things to note here:

This function takes in a mutably-referenced Vec<Option<f32>> instead of a Vec<f32>.

I did this to leverage Rust's Option type to denote to-be-computed points,

rather than using a sentinel value like 0.0.

This, in my opinion, is a better design because the compiler forces us to address

both the None and Some(...) cases explicitly, rather than just assuming a value

exists.

Also, floating point equality has a bunch of gotchas associated with it, which I

wanted to sidestep, and 0.0 is a perfectly valid value for a point, so there's

no guarantee this algorithm couldn't accidentally overwrite previously computed

points in the case of a bug.

The function also takes two indices called i and j - these will control which

subsection of the vector each recursive call operates on.

Finally, I wrote a quick helper function to compute the index of a midpoint,

given an i and j index.

This is pretty straightforward so I'm just going to drop the implementation in here:

Finally, following my textual descriptions above, I implemented the other two functions as follows:

I won't deep dive into every line here, but I'll pick out a couple of specifics to go over.

I compute new_displacement like this:

let new_displacement = displacement * 2.0f32.pow;

This is borrowed from the math in Paul Martz' blog post that I linked above. If you're like me though, you like to work out the math as you translate it to code to make sure you understand what you're doing. This computation is fairly trivial, but it's still a thing I like to do, personally.

Since $x^0 = 1, \space \forall x$ and $x^{-y} = {1 \over {x^y}}$, we can quickly compute the following test values:

smoothness | Multiplicative Factor |

|---|---|

| 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 0.5 | ~0.707 |

| 1.0 | 0.5 |

Ok, so this computation maps smoothness to a value between 0.0 and 1.0,

and as smoothness grows, the resulting computation shrinks, resulting in

new_displacement being less-than-or-equal to displacement.

Makes sense.

Then, there's also this little section at the bottom of compute_points:

points

.into_iter

.filter_map

.

This is a use of Rust's powerful iterators. In short, this function is doing the following:

into_iter()converts ourVec<Option<f32>>into an iterator; this method consumes the vector, meaning we are taking ownership of its valeusfilter_map(...)operates on an iterator, each element is mapped to anOption, and those which yield aSome(...)value are retainedstd::convert::identityis the identity function - since our values are alreadyOption<T>, this works out quite elegantly

collect()collects our iterator back into a collection, we specify a vector here

This is one of the things I really love about Rust - this small expression is doing so much, and yet, it remains quite readable.

Now with the core algorithm out of the way, I need a way to display things on screen.

Enter Nannou

Nannou is a creative coding framework for Rust. If you've ever played aroubnd with something like Processing, Nannou is conceptually similar. If this is all new to you, the TL;DR is: the Nannou framework allows you to quickly and easily spin up programs that produce audiovisual effects. Nannou can also do some cool stuff with lasers and other kinds of AV hardware, but I'm not well-versed enough to write about any of that. In my opinion, rapid prototyping is pretty important when your output is visual. You really want to be able to get something on the screen and build on it as quickly as possible. Nannou makes it very easy to get started with getting something on the screen, via their sketch concept. Then, once you want more functionality, you can use the regular Nannou app.

I'll skip over copy-pasting a ton of boilerplate and just link to a commit here, commit ce5415b has the first iteration of a nannou sketch to draw mountains on screen.

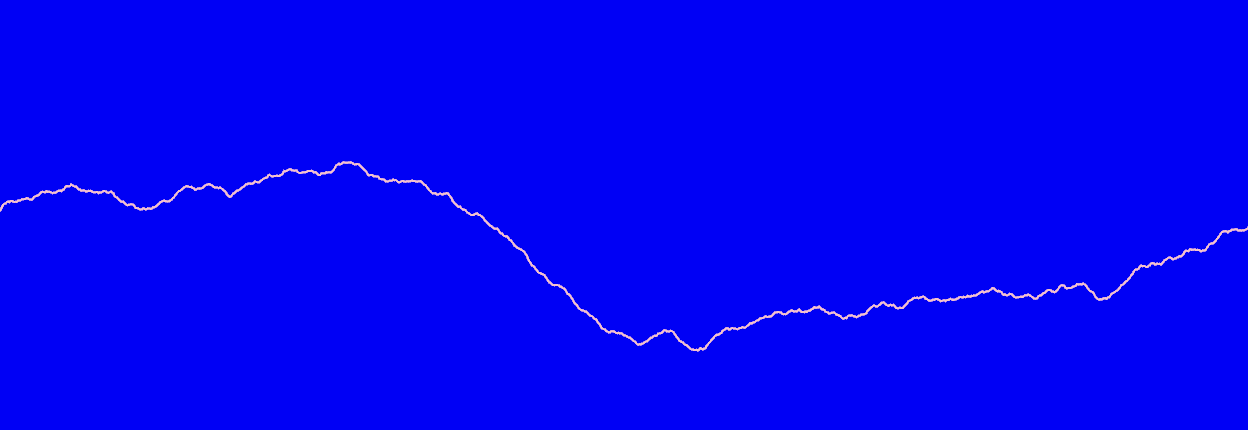

It's barebones, and I personally don't think it's all that pretty, but it works. It generates something that looks like this, more or less:

Filling in the Outline

This outline looks vaguely mountain-like, but it's just an outline. To fill it in, I add a handful of extra points outside the bounds of the screen, like so:

let left_cap = once;

let right_cap = once;

let points = model.points.iter.cloned.enumerate.map;

draw.polygon

.color

.points;

Combining iter::once() and chain() makes it quick and easy to do this.

I also added basic keyboard interaction to avoid recompiling every time I wanted

a new image.

Pressing space now regenerates the mountain image.

That code is in commit 34b4e59.

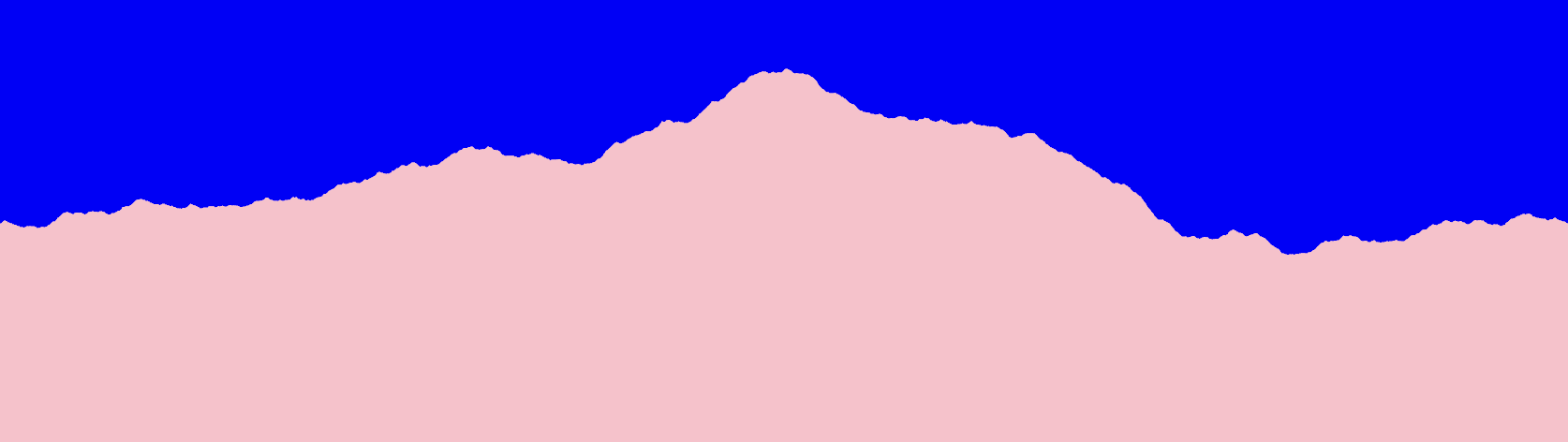

This generates mountains that look a bit more.. mountainy.

Multiple Layers

Now that I had some vaguely mountain-shaped polygon on my screen, I decided to

expand the program a bit more to support layers.

The idea is that a Layer struct could wrap a set of points as well as a

"baseline" Y coordinate.

This would allow me to draw multiple mountain ranges stacked on top of each other,

giving the illusion of distance, or something like that.

While I was at it, I also added in the colorgrad

crate for some nice gradients, and wrote a very simple wrapper type to allow me

to convert colorgrad colors into Nannou colors.

I sample the gradients based on which layer I'm rendering in order to get

evenly-spaced colors for each layer.

That code can be found in commit 51b18ea.

Wrapping it Up (for now)

Finally, I added three very small final adjustments for the time being.

First, I renamed some variables and parameters to read more easily.

Secondly, I adjusted the default screen size to match the dimensions I was after.

Third, I made it so pressing the S key saves the image to the current

working directory.

When all was said and done, I ended up with the following image, which,

at the time of writing, adorns my Mastodon profile:

This version of the code is commit 56e5fe3.

Final Notes

Before I sign off on this post, I want to address a couple of issues with this code. This project is very much so what my CS 4500 professor would have called a "garage program". Essentially, it's in a rough state, it looks like something I whipped up in my garage. Frankly, it kind of is, just sub "garage" out for "living room couch".

Here's a list of things I definitely want to come back and address to make this program more useful and more.. complete?

- there are no tests anywhere in sight; the UI is probably the heaviest lift here, but there's no reason the basic algorithm can't be tested

- everything is shoved into a

main.rsfile; the program is quite small now, but keepng everything inmain.rsis not scalable - it's not possible to specify any parameters; there aren't "magic numbers",

but if the parameters can be named, they can be converted into command line args

- one could imagine specifying steps, displacement, smoothness, gradient, etc.

- there's no non-interactive mode, you need to run the GUI to generate an image

- this is kind-of a limitation of Nannou because it's built around a windowing system, however, it is possible to run one frame then exit

- perhaps in the future, there could be more image generators than just "mountains"

If you've made it this far, thanks so much for reading! I want to continue blogging about this project as I build it out, stay tuned for more.